TL;DR My last day at Mozilla already happened, but I’m still me. I bring together disparate parts to foster learning, spread openness and design for participation. I’m a creative generalist who likes to make stuff, and I’m open to exploring opportunities.

About 5.5 years ago I took a broken dream to the first Mozilla Festival (at the time it was called Drumbeat) in Barcelona. Going to this festival with my struggling project was a last ditch effort, I was hanging on, trying to make it work.

Drumbeat was the place that I was finally able to let go, start over, try again. The people I met there gave me new ideas, they introduced me to a way of working that fit with how my brain operates. Drumbeat lit a fire under me. I met Mozillians.

I’ve resisted the status quo because when I questioned it, I don’t received satisfactory answers. Over the years, Mozillians taught me how to focus my defiance towards a common good. It’s that focus that has cultivated me and my way of being in the professional space.

I believe in open, and I believe that what Mozilla is trying to do for the world is a just cause. Openness can be hard, but in my experience the right thing is always more difficult.

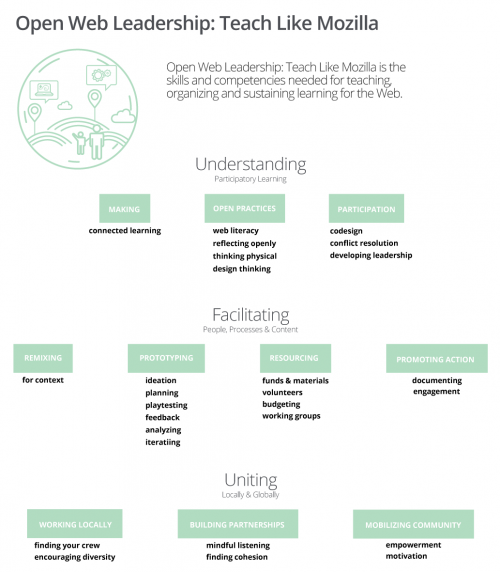

Last Monday was my final day as a paid contributor, and I’m in the process of detangling Mozilla from my own identity. We’ve grown up together in this community. We have rallied around a nascent vision and made it something that is resonating throughout the world. I am proud to have contributed to every aspect of the Foundation’s work – from strategy to learning design to prototyping to evangelism to community management to production – I’ve helped Mozilla innovate in the teaching and learning space.

Our work has inspired people, and I’ll always be a Mozillian. But I want to be more too. Mozilla is a part of me, but it can no longer define me.

I don’t know what’s next for me, and that’s ok. I will continue to think and write and make and learn and fail, and I will continue to embody the open ethos. Even when it’s hard, especially when it’s hard. In the immediate future, I will pause, breathe and take stock. I can literally do anything with the competencies and skills I’ve developed and honed over the years. That feels like a powerful invitation to do the right things.

There is a lot of right in the world. I’m looking for something where I can design learning/engagement opportunities, develop leaders and apply open practices, digital/web literacies and all things geeky. I want to help people/orgs grow, collectively, as they allow me to grow together with them. I want to shift power structures and community dynamics, be a voice for people who need one and just be who I am – defiant, curious, unwavering in the ideals of open.

If you think you have a right thing for me, let me know. You all know how to find me. laura [at] this domain is where you started interacting with me in 2010, and it’s where you can continue to do so. You can also find me on twitter or LinkedIn (or just google me, I’m all over the web). I hope some of you reach out – there are plenty of wonderful memories and new ideas to discuss, and I will always be here for my Mozilla friends.