I wrote this post last Friday as I was thinking through some issues around cultural historical activity theory and legitimate participation. Thought I’d post it here, too, just in case folks were interested.

***************

This week I’ve been organizing a poster presentation on the use of Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) as a lens for thinking about privilege, power, and legitimate participation in high school science. Even though the theory has its detractors, many (Anthony & Clark, 2011; Roth & Lee, 2007; Trust, 2015; Yamagata-Lynch, 2007;)(including myself) have found CHAT to be particularly useful for considering systemic problems (or “tensions” as they’re commonly referred) that (1) inhibit the accomplishment of certain goals (e.g., successful implementation of a one-to-one laptop program) within a social organization (e.g., a school), and (2) end up advantaging certain points of view, ways of behaving, or cultural backgrounds over others. Obviously, any theory or tool that can be used to help researchers, scholars, or practitioners understand problems of practice, especially when they relate to issues of equity, is a good thing to have, but I’ve found that I often have a hard time getting started with a CHAT because the concept of “activity” is a slippery one to define.

Technically, “activity” refers to any kind of goal-motivated behavior. This is different, however, from what we might call a “task” because, as it’s been theorized, an activity, unlike a task, takes place with a social context. And context matters. Consider the task of getting dressed. This task has a very different meaning depending on when and where it’s done – telling someone that you got dressed in your own room in the morning might earn you a totally different reaction from telling them that you got dressed in a stranger’s house or a public place in broad daylight. It’s the context that makes this task seem common and mundane, or strange and embarrassing. (Really, in a way, this means that all tasks are activities, because when is a task not contextualized? But I digress…)

“Context” is also a slippery term, because it can include pretty much anything. Socioculturalists might say that context is made up of everything that exists in a place in the moment, as well as everything that led up to that stuff being there for that moment – the history of the physical objects, the cultural values that give those objects meaning, the arrangement of objects and people in the setting… each of these things matters in how one decides to use a tool and for what purpose, as well as how one’s behavior gets interpreted.

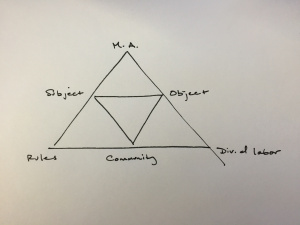

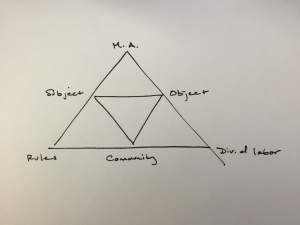

All of these nebulous characteristics of the activity context intersect and interact with each other, and together, they make up the activity “system.” Without getting to deep into the theory of it all, one of the advantages of CHAT is that it gives us a way to divvy these characteristics into six categories: subjects (the individual or group performing the task), the object (the goal of doing the task), mediating artifacts (the tools that are used to achieve the goal), rules (normative or expected ways of doing the task), community (the large social arrangement/organization in which the task is being performed), and the division of labor (the roles of the people/groups within the larger social organization for accomplishing the task). Now, I don’t know about you, but at this point, my head starts to swim with all of these terms and trying to figure out who is doing what and why and with whomever and with what tools and where did those tools come from, anyway? This is when I take out a pen and paper and start trying to draw things that can help me visualize what my brain is trying to keep track of. Luckily, CHAT has this canonical representation that it seems pretty much everyone who talks about activity theory uses, and it looks like this:

Look at all those triangles! What’s lovely about this representation is that it gives the impression that everything here is interconnected. And that’s the point. Don’t you just love it when simple graphics can convey complex ideas? Yay CHAT. Go team!

So that’s all good and awesome, until you start trying to think about what constitutes an activity. Where did the activity begin? Where did it end? Depending on the grain size of the activity, the various nodes might look completely different. This is very problematic when trying to consider complex activities like implementing a curricular intervention or a district-wide technology initiative. Each of these long term activities is made up of possibly infinite, but meaningful, activities (Lisa Yamagata-Lynch wrote a fantastic piece that addresses these same dilemmas).

In my dissertation, I used CHAT to look at the different ways in which students used technology in a one-to-one laptop classroom, and early on in my analysis, I found myself drowning in a pile of papers with little triangles sketched on them. My problem is that I was trying to figure out how to capture the essence of an activity when it wasn’t explicitly demarcated for me. An activity could be as long as a subject unit, or as brief as recording a single phrase of text from a lecture slide. It was up to me to decide how each of these activities were significant, and which ones related to my research questions. It’s part of that subjective research experience that gives us qualitative researchers limited street cred among our quantitative, objectivist, and positivist colleagues. But that’s another story all together…

Okay, we’re still not done. I said something earlier about CHAT being useful for looking at systemic problems or “tensions.” Let’s get back to that now.

So, the idea is that once we’ve charted all of the constituent “nodes” of the CHAT triangle for a given activity, we can go about examining how elements of these nodes interact with each other in ways that either help the subject achieve the goals of the activity, or inhibit it. For instance, let’s say you (subject) want to use the Internet (mediating artifact) to help you look up the score of a basketball game (object), but you don’t have access to the Internet. We might represent that as a tension between the mediating artifact (Internet) and object (looking up a basketball score). Or let’s say you’re a teacher (subject) and you want to learn about a new software tool (mediating artifact) that you might think would be particularly helpful for a certain lesson you are trying to teach (object), but there’s no one at your school, like a technology integration specialist, who can help you learn about or implement that software into your lesson planning (division of labor). We could represent that as a tension between the division of labor and object of the triangle. To my knowledge, there isn’t a single convention that is used to represent tensions on the CHAT triangle, but some common examples include placing an “x” or lightning bolts along the side of the triangle where the tension exists.

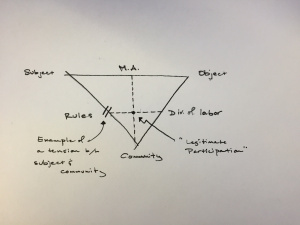

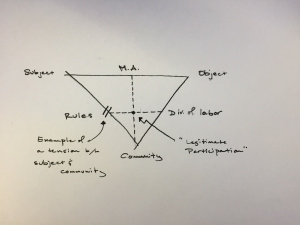

Now, these are relatively simple examples of tensions, so you might already be thinking, “What about more complex problems, such as a tension between rules and division of labor? Or tensions that emerge between interacting activity systems? How can we represent these?” That’s a good question, and it’s where I find myself now. The problem I am having at the moment is coming up with a way that gives credence to how the various elements of activity systems mediate each other, but also provides an elegant way of showing how a tension impacts the object of activity, as well as introduces the concept of “legitimate participation” (Lave & Wenger famously coined the term “legitimate peripheral participation” to describe how individuals are inducted into communities of practice) I feel like much of what has been done to date to represent complex tensions doesn’t adequately (or at least cleanly) show these in, say, the way a line graph can show how the amount of something increases and decreases over time. In preserving the sticky image of triangles, what I’ve been playing with is something like this:

What this does for me, is highlight the centrality of issues around “legitimacy” in activities, as something that is influenced (or even governed by?) the relationship of one’s participation to the privileged norms of behavior (rules), roles (division of labor), and use of tools (mediating artifacts) of a social group (community). I’m not convinced that this does any better job of achieving that than the standard CHAT triangle. But if anyone out there has any ideas, I’m all ears (and triangles)!