Introduction with Bill Penuel [Webinar]

Tuesday, April 7, 2015 9:00 AM PDT

Facilitators: Dixie Ching, Rafi Santo

Participants: Bill Penuel, Professor of Educational Psychology and Learning Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The first webinar of the Design-Based Research strand focused on the goals, purposes and argumentative grammar of design-based research, and presented design-based implementation research as a nuanced approach. Here my take aways.

A Few Points

- Design is always a political act, even if it is not explicitly stated.

- We have to ask: Who is at the table? Whose future is valued?

- DBR is still evolving and in flux

- Be intentional about purposes and questions

- Listen to the classroom setting and the questions that are emerging.

- Iteration and changes of direction are common.

- You need a big team to address all purposes at once.

- Take things off the table.

- Apprenticing with experts who are skilled and have experience in the kinds of research can be invaluable experience.

- DBIR is always a collaborative effort.

Goals and Purposes of Design-Based Research

- Design-based research studies interventions, how the intervention is designed (and evolves), and how that intervention supports the intended outcomes of the design. Doing design is a way to learn about learning, and combining design and research given the opportunity to study learning and to create the structures for supporting learning. One example would be the creation of an innovative way of learning a particularly difficult concept at an earlier age than it was possible before the innovation.

- Design-based research develops local and humble theories that are closely tied to the specific context of the design-based research intervention. Humble theories can relate to learning and design. For example, Through the active and interventionist engagement, design and implementation of innovations in real world settings, such as classrooms, researchers can get better understanding of how learning is done in this context. This gives that an opportunity to develop, for example, local theories of learning. At the same time, a close look at how design was organized in this context can reveal a better understanding of theoretical perspectives about design.

- Design-based research give knowledge about implementation. Particularly design-based implementation research focuses on how to anchor, scale and sustain design-based research innovations across a wide range of contexts. Studying adaptations can provide knowledge on how to implement design-based research before, during and after the fact.

Panuel and his students are working on a theoretical perspective of how to organize collaborative design within design research, including to what extend collaboration supports teacher’s agency. One question includes: How should design be organized to expand teacher’s agency on what they may be able to teach? This might change how we see the the metaphorical notion of design, introducing organization as a new way of looking at design-based research.

The Argumentative Grammar of Design-Based Research

Argumentative Grammar refers to the notion of the logic that guides the use of a method and support of the data it provides. This does not relate to the strength of an argument, but rather something related to your methodological approach that can be isolated from context and can be appreciated by anyone outside of your field of research. The argumentative grammar of design-based research has not been fully developed yet. It is a family of approaches that moves towards a set of standards and tools to help evaluate claims. This is meant when people say that design-based research is an evolving field.

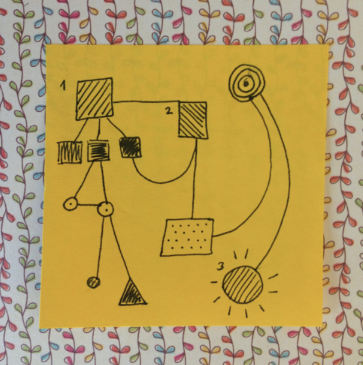

To help move this forward, Sandoval introduced the idea of Conjecture Maps. The idea is that researchers make their suppositions about learning as explicit as possible in the beginning in order to be able to backtrack how they are embodied in the form of the design created through design-based research. This is a way to critique theories and designs, as it leaves room for questions. The opportunities for critical conversation about the results of design-based research studies can help strengthen the argumentative grammar of the area of research.

Penuel added the idea to brainstorm ideas of how designs may fail, that is how a design may be used in unanticipated ways that would not lead to the kinds of learning we were hoping to see as a result of the design. While we cannot anticipate all unintentional uses in advance, imagining some possible failures can help address possible biases towards ones own work.

Yet another way would be to build on prior design work in a similar area. This can help knit the field closer together and form tighter justifications for why particular decisions were made.

Design-Based Implementation Research

Design-based implementation research relates to the critiques on what it takes to scale an innovation. There are many different things that can come out of a design-based research project. Even if the project does not go well, one can share valuable insights. Further, there is no need to completely abandon the innovation. The idea here is to think about how to adapt the innovation and at the same time to consider how the context could be rebuild. DBIR shifts focus on design across levels (e.g., professional development, environmental factors, infrastructure etc.) and looks at what it would take for the innovation to be widely and effectively implemented. This systems look is considered to help see how innovation may fit, and what would need to change (in the system and/or the innovation) to make it work without compromising the essence of the original motivations.