A post by Alejandro Andrade

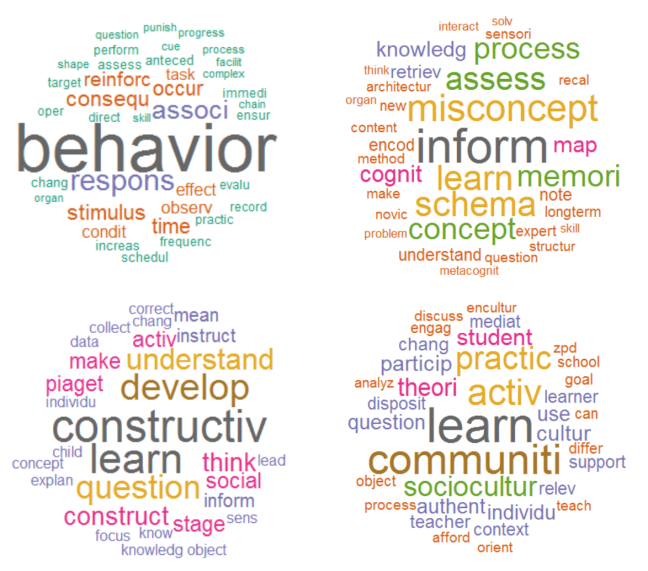

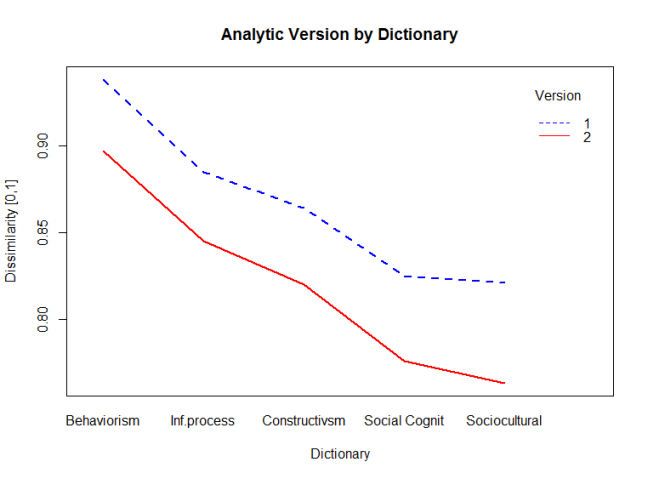

After having the opportunity to explore the use of a text mining approach to analyze information in a design-based research project about using video to support pre-service teachers’ ability to notice (Van Es & Sherin, 2002), I have three major ideas to share. First, these data-mining techniques are flexible and powerful tools, and yet one should be aware of several of their limitations. For instance, the stemmed words in a text document are but proxies of participants’ conceptual engagement, but these might be a rather distal than proximal type of evidence. The bag-of-words approach, the one used in my analysis, overlooks a great deal of information that might have been relevant to help tease apart more nuanced hypotheses. Nonetheless, the approach, however distal it might have been, did provide relevant evidence given the context of the present study, for instance, the relationships between the learning theories and the student analytics, and these latter and the experts’ analytics.

Second, while the bag-of-words is one text mining approach, it is not the only computerized technique available. Indeed, other more powerful tools can supplement or replace such an approach. For instance, some computerized linguistic analyses exist that can provide measures of coherence and cohesion in text documents. One of such techniques is the Coh-Metrix (Graesser, McNamara, Louwerse, & Cai, 2004), a free online tool that provides more than a hundred different indices with text characteristics. Among others, Coh-Metrix provides information about text easability, referential cohesion, content word overlap, connective incidence, passivity, causal verbs and causal particles, intentional particles, temporal cohesion, etc. With this tool one can supplement the findings about differences and similarities between the students’ and experts’ analytics, for instance.

Third, I believe that the incorporation of computational techniques to the researcher’s toolkit is bound to gain traction in the learning sciences. In particular, as researchers adopt design-based research methodologies (Cobb, Confrey, Disessa, Lehrer, & Schauble, 2003; W. Sandoval, 2014; W. A. Sandoval & Bell, 2004) that demand a sequence of test and refine iterations, they might consider having tools in their belts that can allow swift and reliable understanding of their results. Unlike other slow qualitative coding-scheme-based approaches that require inter-rater reliability, content analytic tools such as the bag-of-words are much faster and consistent. Also, these quantitative tools are useful with only a small group of students or with larger samples of various hundreds or even several thousands of participants. This doesn’t mean that traditional coding schemes are not good, or that we should stop caring about them. On the contrary, I believe that both approaches can work in tandem, where computational techniques provide a first glance at the data for a quick and dirty pass of analysis that can inform the research team on how to adapt and refine the design, and then, when resources allow, researchers can go deep into the data and examine the nuances of student learning interactions.

References

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., Disessa, A., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2003). Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 9.

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Louwerse, M. M., & Cai, Z. (2004). Coh-Metrix: Analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(2), 193-202.

Sandoval, W. (2014). Conjecture mapping: an approach to systematic educational design research. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 23(1), 18-36.

Sandoval, W. A., & Bell, P. (2004). Design-based research methods for studying learning in context: Introduction. Educational Psychologist, 39(4), 199-201.

Van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. G. (2002). Learning to Notice: Scaffolding New Teachers’ Interpretations of Classroom Interactions. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 10(4), 571-596.