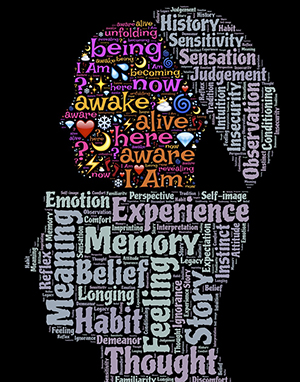

In a previous article written for my Digital Media & Learning Research Hub blog, “Striving for New Ways to Learn How to Learn,” I wrote about co-learning as the heart of the connected learning experience. We have heard quite a bit about the limits of the “sage on the stage” approach and the dawning of new affordances in teaching with the “guide on the side” model. It goes without saying that a changing relationship to authority and hierarchy in the classroom is no small feat. It can certainly induce anxiety for all involved — the teacher must relinquish familiar control, the student must claim learning on terms that are not prescribed by anyone else. Unlearning is not easy for all involved. It is a radical shift setting everyone a bit adrift on an unknown course. But, this kind of paradigmatic sea change is about transformation. Transformation is indeed a complex, energy requiring developmental process. Like all meaningful change, I suspect it cannot occur without some necessary discomfort. And, I am experiencing this now first hand.

In a previous article written for my Digital Media & Learning Research Hub blog, “Striving for New Ways to Learn How to Learn,” I wrote about co-learning as the heart of the connected learning experience. We have heard quite a bit about the limits of the “sage on the stage” approach and the dawning of new affordances in teaching with the “guide on the side” model. It goes without saying that a changing relationship to authority and hierarchy in the classroom is no small feat. It can certainly induce anxiety for all involved — the teacher must relinquish familiar control, the student must claim learning on terms that are not prescribed by anyone else. Unlearning is not easy for all involved. It is a radical shift setting everyone a bit adrift on an unknown course. But, this kind of paradigmatic sea change is about transformation. Transformation is indeed a complex, energy requiring developmental process. Like all meaningful change, I suspect it cannot occur without some necessary discomfort. And, I am experiencing this now first hand.

As a part of the Connected Courses community and, more recently, with Hybrid Pedagogy’s #moocmooc network, I have explored the topic of co-learning with many inspired colleagues/practitioners throughout the world. We continue to conduct open conversations and gather excellent resources regarding co-learning. Along the way, these engagements have prompted me to dig deeper, considering what co-learning methods truly challenge my comfort zone, pushing beyond the practices that I have already established. The truth is, for some time now I have incorporated open, networked, and connected practices in my teaching. As a matter of standard (intuitive) practice, I have always made student agency, student choice, and student instinct a listening/actionable priority. I suspect every seasoned teacher has a kind of momentum which is rooted in the purposeful design of the learning experience. One learns what “works,” what readings/conversations/exercises equate with memorable and meaningful moments. It is most definitely easier to stay the course, especially when your well tested methods have yielded positive results. So, if a class has worked really well in the past, why redesign the experience? Said another way, why mess with success?

This semester, I am revamping/uprooting a course that “works.” I am taking a great leap of faith because I am not sure these changes will yield the same successful results as the previous version. “Writing Race & Ethnicity” is a cross-listed undergrad/grad class in my Department of English Studies at Kean University. This is a course about story, the story of the Rhetoric(s) of Race and Ethnicity, and its structure and function in the places we live — home, school, work, the world. It is a course about writing, about the writing and the re-writing of race … of my/your identity. It is a course that has always been incisive, empowering, and inherently personal. With the affordances of a networked classroom, we have the collective power of engaging in this conversation publically. And, although this presents some “risk,” this is not what I find most challenging. The really difficult part of this revamp is relinquishing my own version of what works. In short, I will not outline their course of study, I will not tell them exactly what to read, and I will not list their learning outcomes. My students will do all of that — through reflection, collaboration, and negotiation with each other. I will guide from the side.

Each course has its own chemistry, and I guess for some educators, courses are almost like unique children we will always cherish. (Each class has its own special charms, produces a unique learning community …a great class leaves us with the trace of remarkable memories). I am fortunate to be teaching a course this semester that I have successfully taught before and I have always loved to teach. I must admit that when it comes to my course rotation roster, I am always happy when it is time to teach this one. But, this semester, my new approach feels like I am hanging on a limb. I am uncertain. I feel vulnerable. I fear my experiment will fail. (Despite the fact that I know we really need to rethink this notion of failure.) So why do this? Because somewhere down in my gut I know that vulnerability is the heart of learning, and I know I need to learn too. The students just might think that by relinquishing my directorial lead, I am exempting myself from the “real work” of being a professor. But, I can assure them that this guiding (but not professing) work is much more difficult. It requires me to be responsive and candid, and generous without reassurance. As colleagues Maha Bali and Jesse Stommel have recently written:

In the Introduction to Teaching to Transgress, bell hooks writes, “any radical pedagogy must insist that everyone’s presence is acknowledged.”(8) She describes the process through which we become self-actualized in the classroom. “Teachers must be actively committed to a process of self-actualization that promotes their own well-being if they are to teach in a manner that empowers students.”(15) And, it isn’t just that students should be empowered to show up as full selves, but that teachers must as well, in order to model, but also to show the kind of care for the work that only comes when we make ourselves at least somewhat vulnerable.

Connected learning boils down to risk taking in the end. To quote colleague Jade Davis from her recent DML blog post, “I think the biggest risk in connected learning is Not Trying.” Mostly, I find that co-learning is somehow linked to a kind of “life attitude.” When I became a mother, I realized quickly that everyday my children teach me myriad vital things. These brand new people, who have so little experience, are in many ways masters of what is significant in life. A truly wise person learns from every person he or she connects with in the most unforeseen moments. This is of course the soul of co-learning. And, perhaps it is also the seed of equity and justice. But, it is not necessarily easy to maintain this outlook, especially as we continue to navigate institutional demands, programmatic expectations, and expected outcomes.

So why all this talk of leaps and risks? I truly believe there is much at stake in what is considered here. Institutional change that matters must generate first from the heart of the learning communities we design. These co-learning steps we are taking together are indeed the seeds of a kind of personal growth that can play an important role in contributing to a healthy citizenry. The transformative force for equity and justice in society lies first in the way we come together to learn. In the ways we are educated lies a foundation for how we meet the world. Striving for equity in the classroom context will set a course for collaborating and negotiating — a habit that will certainly yield fair-minded moments in unforeseen futures. A connected co-learning model is essential not just for reimagining education, but more importantly, for realizing our democratic aspirations.

P.s. A helpful resource for preparing to “flip the syllabus”: Fieldnotes to 21st Century Learning. Some resources that helped me rethink the terms of evaluation (grading): Miriam Posner’s lucid outline of her “contract grading”; Gardner Campbell’s APGAR system for learning self evaluation and Steve Greenlaw’s resulting criterium for grades.

Banner image credit: Vishal Patel

I must mention that I have successfully taught this “Writing Race & Ethnicity” class in the past. These earlier iterations have followed a more traditional design. I have distributed a well-honed syllabus which included significant readings in the fields of both race theory and literature. I have provided a clear break down of course expectations, including learning outcomes and class assignments. By all accounts, my earlier versions of this course have had clear favorable outcomes. The work submitted by students has been significant, the discussions have been memorable and engaging, and the class chemistry has led to a true feeling of meaningful community. Some of my favorite teaching memories are attached to this particular class in its earliest form. But, despite this successful track record, this time around, I stepped back, and really thought about the point of this class.

I must mention that I have successfully taught this “Writing Race & Ethnicity” class in the past. These earlier iterations have followed a more traditional design. I have distributed a well-honed syllabus which included significant readings in the fields of both race theory and literature. I have provided a clear break down of course expectations, including learning outcomes and class assignments. By all accounts, my earlier versions of this course have had clear favorable outcomes. The work submitted by students has been significant, the discussions have been memorable and engaging, and the class chemistry has led to a true feeling of meaningful community. Some of my favorite teaching memories are attached to this particular class in its earliest form. But, despite this successful track record, this time around, I stepped back, and really thought about the point of this class.